Fascism is neither remotely in the past, nor remotely in the future. Sadly, we do not live in a “post-fascist” present

Several commonplaces, almost cliches, have emerged from a range of journalists and intellectuals in the face of the rise of the far or radical right in parts of Europe and North America over the last six years.

One is to talk little about the far right as a category at all, but instead about “populism” assailing the rational liberal centre. This “populism” then has a right and a left face, but they are just aspects of a general substrate of evil.

Thus the frequent interventions of the US-based Dutch academic Cas Mudde and his efforts to define a discipline of “populism studies”. Unsurprisingly, it is very popular with liberal ideologues, such as the Guardian newspaper in Britain, who want to throw back the radical left while voicing opposition to the far right. This theorisation allows them to consider the former the conjoined twin of the latter and to slur it accordingly.

Another commonplace has been to collapse serious investigation of the range of forces and strategies on the radical right. Instead it has been to project a levelling generalisation in which there is a “new authoritarianism” or “authoritarian populism”. It is held to be a meeting point of traditional right wing forces dabbling in populist technique on the one hand, and once fascist forces moderating to the same convergence on the other.

That case was put a couple of years ago by the distinguished British historian of the Third Reich Richard Evans at a lecture in Athens.

There is not a fascist threat in Europe (at least west of the Danube), he said. That is due to radically different objective circumstances from the 1930s and to a profound shift in the nature of the far right compared with then and with as late as the 1970s and 1980s.

It has evolved into an essentially conventional and parliamentarist authoritarianism. Nasty, contaminating of politics, but not at all like the interwar insurgent threat to democracy. Parts of Eastern Europe may be different, he argued. His explanation was in essence the liberal theory that the Communist period had replaced one totalitarianism with another, thus preventing the post-war embedding of parliamentary democracy that happened in Western Europe (the Iberian peninsula and Greece have to be “non-western” here).

Even then, the threat in the East was from the governmental-authoritarian right of the likes of Viktor Orban, rather than from something closer to classical fascism. (Ukraine was not mentioned.)

Evans’ intellectual integrity is such that he readily conceded that Greece and the then very strong Nazi Golden Dawn did not quite fit his scheme. Others who have put cruder versions of his analysis have tended just to ignore the counter examples in posing a singular convergence of a new authoritarian right in which fascism is at most a fringe politics and strategy – a possible future threat, but not now.

There is a grain of truth in talk of a prominent “authoritarian right” model. But I think it is one-sided and overstated.

Fascism and a typology of the far right

The big problem is that it takes one trend, ignores others that are moving in a specifically fascist direction, over-generalises, and fails to grasp the contradictory dynamics and thus the complexity of the picture.

I tried to highlight some of that in this piece, which originally appeared in Jewish Socialist magazine in Britain. Though three years old, I think it is still of some use in how to approach a more integrated and dialectical analysis of the far right and its fascist components. It argues:

“There is a range of far right formations seeking to build out of the European crisis. The fact that they all consciously occupy a space to the right of the mainstream centre-right parties means they share a very general ‘radical right wing’ character.

“If you want to build in that political space you need constantly to demonstrate in word and in deed that you are ‘more radical’ than mainstream parties of the right. And those are increasingly turning to the politics of racism and scapegoating. The authoritarian centre-right governments of Poland and Hungary are but hardline variants of that wider phenomenon. Beneath the general character of the far right, there remain important differences of strategy and ideology.”

Among other examples in sketching a “typology of the far right” it looks at the AfD in Germany. Back in 2016 there was a widespread view in journalistic-political circles that in advancing electorally the AfD would evolve to a simple parliamentarist hard right force. It might be brutish, racist and with authoritarian tendencies, but not so substantially different from the Bavarian CSU, the profile of whose voter base it largely shares.

In fact what has happened is not a simple process of “domestication”. The AfD has simultaneously gathered electoral support and radicalised. There are two tendencies, not one. That has given rise to internal contradictions and schisms of various kinds.

But those have boiled up and produced actual splits only thanks to the pressure of the movements in Germany against fascism and racism. And at the heart of those movements is an analysis and related strategy that accurately capture the AfD as containing a big fascist cadre and having fascisising tendencies. It is not just another racist, neoliberal party with perhaps a dash more authoritarianism and a “populist” profile.

Further, it exists in a symbiotic, though contested, relationship with a significant, violent neo-Nazi, fascist scene. The German internal intelligence puts the number of “right wing extremists” at 24,000. The majority of them are relatively open in saying they are prepared to use armed violence for political ends.

Additionally – and this is a point also made very well in Ugo Palheta’s excellent book, The Possibility of Fascism – even fascist parties such as Marine Le Pen’s RN, which has publicly “domesticated” or “de-diabolised”, face a problem.

When they make big electoral advances they are still finding themselves locked out of wielding political and executive state power. For all Le Pen’s attempts to present herself as “everywoman” in 2017, and renaming her party, she got only a handful of MPs, fewer than each of the Communist Party and La France Insoumise on the radical left.

That feeds a potent argument from those who wish to promote more “militant”, directly fascist strategies – and those people exist at the heart of the RN. It is that conventional methods and seeking to hegemonise only the right can get you only so far. To break through you need additionally a much more combative street organisation in anticipation of further political breakdown and extreme polarisation. You need to demonstrate extra-parliamentary force if you are to crack open the old political system.

That means you have to harden a cadre in that direction, as Jean-Marie Le Pen used to do.

The immanence of fascism

Similar dilemmas face the FPO, with its fascist roots, in Austria, or Matteo Salvini’s Lega in Italy. He did not succeed in forcing a new election by bringing down the previous government this summer. He has called on supporters across Italy to descend on the capital this month to protest against the new one, a kind of postmodern March on Rome.

That tactic is incubating of actual fascism and brings frustrated Lega supporters into a common space with the outright fascists of CasaPound and the Brothers of Italy.

A newly elected MP of Vox in Spain has resigned saying that what she thought was just a national conservative, Spanish integralist party turned out to have an “extremist, anti-systemic” core.

So there are both fascisising, radicalising dynamics and – in even the most hybrid “post-fascist” or “new authoritarian” formations – fascist cadres who want to push in that direction.

These are not future evolutionary potentials, but current objective and subjective actualities.

This entire aspect and the morphing affinities and networks on the fascist or fascistic right are flattened out of a picture painted as a simple convergence around a post-fascist, “new authoritarian” right that bundles together a range of phenomena in the manner of the theorists of populism.

Another aspect of that flattening is mainstream reception of Nazi terror atrocities such as in Halle, Christchurch, Pittsburgh, the murder of Labour MP Jo Cox…

There is commonly a three-fold separation from the fascisising or actual fascist forces of the far right.

First, the evident racism, misogyny, Islamophobia and anti-semitism are acknowledged (to varying degrees). But it is frequently put down just to bad ideas that are swirling around. The worst instance of this is how official politics in Britain treats the Nazi murder of Jo Cox as some simple extension of incivility in political discourse.

Second, where the wider far right is rightly put in the frame it is solely at the level of it emboldening through words, and thus legitimising, the “lone wolves” who then go “too far”. That is put in a way that everyone can safely condemn – even German interior minister Horst Seehofer, who says, “There is no place for Islam in Germany.” The actual material mechanisms between the Nazi violence and the fascising or fascist tendencies within the radical right as a whole are rarely investigated, unless there is something like the intervention into the Golden Dawn trial in Greece. We shall see if they are explored over the Halle terror attack, though the German state’s performance over the last 15 years suggests not.

Third is a frequent fixation upon the online mode of what the security state has termed “radicalisation”, coined at the start of the War on Terror. That this is a common factor from the Christchurch to the Halle Nazi terrorists posting livestream video of their murders is beyond dispute. It requires forensic examination, and I’m looking forward to Jeff Sparrow’s book this month that promises to do just that.

But we should be careful of exaggerating this novelty – which is but a product of technological development. The murderer of Jo Cox received through the post from US Nazis a copy of an infamous white supremacist tract, years before online chat rooms and the web.

The European neo-Nazi scene in the 1980s and 1990s networked through badly published pamphlets and books obtained from secretive PO Box numbers. Online communication accelerates enormously the speed of communication and dissemination.

But it is a simplistic picture to portray the outcome as just twisted, embittered young men getting radicalised online as isolated individuals in some grotty basement.

For the same media of communication mean that forces organised or aiming to be networked in real life have sophisticated methods to help them do so. What French activists have named the “fascho-sphere” means that those in far right formations who are frustrated at the slow pace of “legal-conventional” methods can more easily connect with others seeking “militant” radicalisation.

Not simply a passive process, but an active mechanism – and one which means that there is within even avowedly “constitutional” radical right forces a much greater porosity and intermingling with actual neo-Nazism than might outwardly be apparent.

The Christchurch Nazi terrorist networked online but also met in real life in Europe with the leader of Generation Identitaire and other fascists.

The “actuality” of anti-fascism

That the racist and far right poses a serious threat is common ground on the left, and among sincere democratic liberals.

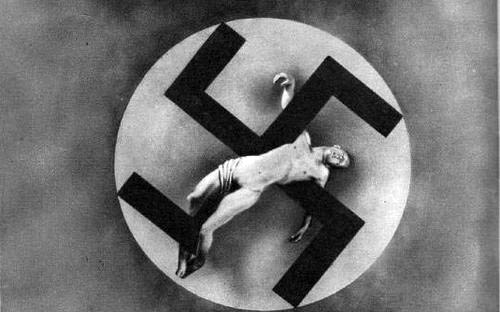

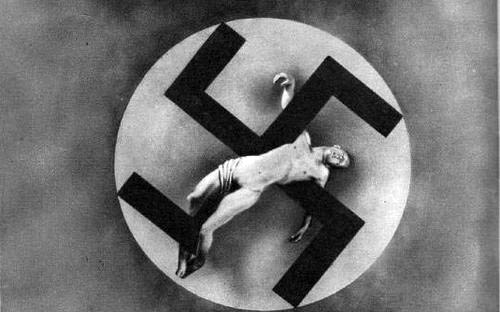

If one mistake in responding is to regard all forms of reactionary radicalisation as fascism, another is to lose the category of fascism altogether. Or, which in practical politics approximates the same thing, to regard it as remote – remotely in the past or remotely in the future.

Rather, I suggest, it is better to recognise the immanence of fascism. By that I don’t mean the prospect of waking up tomorrow literally to find a fascist seizure of power in the manner of a Mussolini or Hitler.

It is instead that the processes producing actual fascist, material mechanisms are neither in the past nor at some point in the future, with us inhabiting a world of the “post-fascist right”.

They are generated now within the ugly family of the radical or far right – either under their own flag as distinct fascist forces, or as outgrowths of an authoritarian right running up against severe limitations and political dilemmas.

Halle, Christchurch, Pittsburgh… none of them are aberrations brought by “gamification” or the dark web. They are horrific expressions of a contemporary fascist dynamic within a wider far right, and in turn of reactionary efforts of all kinds to buttress a failing capitalist system against radical left insurgency.

That all calls for an “actuality of antifascism” in the course of the radical left confronting reaction and racism of all kinds.

That requires an acute analysis, alert to the shifting and conflicting currents in the situation, and rising above the conventional (and often faddish) over-generalisations of so much journalistic and academic analysis.

By Pluto Press (200 pages | 5 x 7 3/4 | © 2015).

By Pluto Press (200 pages | 5 x 7 3/4 | © 2015).